Kim Stoddart explains how a deep connection with the natural world has informed her life and that of those around her…

For a period of weeks, nudging into months, I still recall clearly how I retreated during my lunch breaks at secondary school to a clearing nestled within the sanctuary of trees in a nearby park. The stillness, permeated only by the song of birds, the rustling of the leaves in the breeze, provided me with a deep sense of calm. A balm against the pressures of exams, of growing up and all that was now expected of me. A soothing panacea against conformity; in all its guises and in particular the acute, at times crushing strain of assumptions to look, talk and act a certain away among my peers, no matter what I felt inside.

Time out in nature helped me deal with it all. Helped me to to unravel the quandary of what was required; enabling me to fit in and find my place.

When I was running a busy PR company in Brighton, the only natural world I experienced during the average day consisted of a scrappy-looking grass verge on my walk to the office and back. So I sought solace in the growing of fruit, vegetables and herbs in my small back garden. The nurturing of seed into germination and plants that would grow on to produce food helped provide a connection with the elements, with natural cycles that I found highly beneficial to managing the stresses of my work.

The same applies for me now as a journalist and magazine editor. If I’m stuck on an article, a work conundrum, or feel overwhelmed by a fit-to-bursting inbox, I know that by stepping away and gardening, I will be much more effective overall. Doing so, provides me with space against the barrage of busy pressures and long ‘to do’ lists, which means I can see the wood through the trees of my workload and life in general.

Having seen first-hand for myself how therapeutic gardening can be, it was only natural then that when my youngest son, Arthur was diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder at the age of three, it was the gardens to which we often turned. As my son was struggling to deal with (and adapt to) the sensory overload of much of modern day living; loud noises, developmental targets and societal expectations, behavioural rules and regulations; nature provided a soothing relief on a scale I wouldn’t have previously believed possible. When Arthur had a meltdown, walking outside tuning into the sounds of nature provided almost immediate emotional regulation. In the early years when I was struggling to get him to eat fruit and vegetables, being able to pick fresh berries, peas or tomatoes et al from the garden gave him more ownership over the process of eating. This in turn provided positive stimulation which helped him let go and he continues to eat a wide range of produce to this day.

My experiences with my son opened my eyes to the true, powerful potential of meaningful time spent in the green outdoors. Actually, Arthur, and understanding about this multifaceted spectrum disorder, has opened my eyes to so much and turned perceptions on what is normal (and what is not) for me often entirely on their head. As it happens, there’s a great personal empowerment to be had in this.

It’s no wonder then that the mental health benefits of gardening engagement continue to resound in the media and public consciousness. Or that involvement in positive, outdoors activities happen to be high up the to do list when it comes to the recent Governmental shift towards social prescribing via the NHS. Or indeed that this green-fingered-pastime is increasing in popularity across the board with houseplant growing the new hot trend for millennials. With the dominance of 24/7 media and social media vying for our attention and telling us how to look, act and be, there is so much pressure now, a daily bombardment of information on what success and indeed normal should actually be. It’s hardly surprising that more and more people are seeking solace in altogether simpler, more wholesome less aesthetically pressured ways.

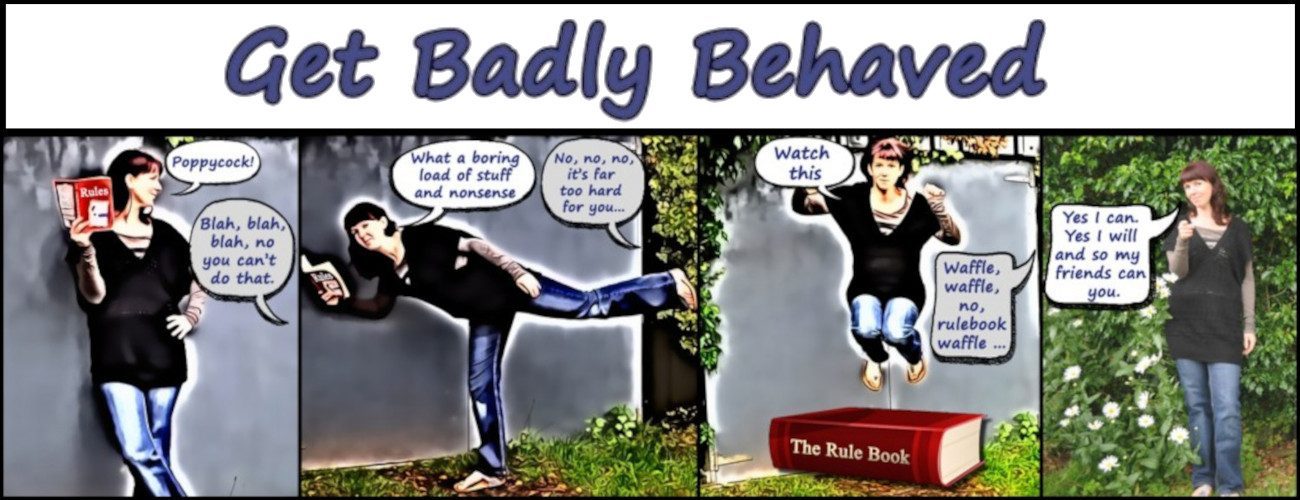

Living with the sensory burden of 21st Century living is hard enough for your neurotypical individual, let alone for those on the autistic spectrum where each sense can be over or under simulated in a myriad of different ways. The noise of everyday living takes on a whole new meaning when it comes to ASD. Combine this with the fact that a diagnosis so often brings with it a perception of ‘can’t do’ focused on the challenges and barriers to so-called typical behaviours (rather than what can be done) and you can see why just 16 percent of the 700,000 people on the spectrum in the UK are in paid, full time employment. In reality, over three quarters (77 percent) of those not engaged in work would actively like to be involved in something.

The tide has already begun to shift in perceptions of autism, and barriers to employment are in the spotlight with the recent emergence of 16-year-old climate activist, Greta Thunberg who, alongside meeting with party leaders across Europe, talks about her Aspergers and being different as helpful to her mission. She actually calls it a gift and believes she wouldn’t have started her school strike that sparked a global movement without it…

Whilst Greta is unique in some ways, in others she is not because she hasn’t gone down a normal career path, she has forged her own and she has done so with gusto. Yet, all so often we expect people with autism to fit into societal perceptions of normal, which is something that a non-neurotypical mind will often find it extremely hard to do. Lack of employability skills come almost preordained with a diagnosis and an expectation bar that is focused on the challenges of ASD and a result set often so incredibly low across the board. The knock on cost to the NHS and services is at present large and it’s telling that autistic adults with a learning disability are nine times more likely than the general populous to die from suicide.

Could there be another way? I increasingly believe so. Everyone is capable of something and the opportunity to be involved in meaningful activity, paid or otherwise, is arguably essential to individual wellbeing. I think that by affording the opportunity for emotional regulation from the everyday noise of can’t do expectation and by honing instead on what can be done, this can help build all so vital confidence to enable some non-neurotypicals ideas of career and possibly self-employment ventures of their own making to blossom and grow.

Gardening and outdoors activities provide a beneficial balm and backdrop, not least of all because nature doesn’t judge or expect us to fit into boxes or behaviours, quite the opposite. It is full of curves and quirks and altogether less polished edges which affords no judgement or prior perceptions. It instead provides room for us all, with a valuable role, no matter our differences or perceived limitations.

A version of this article first appeared in the Lancet Medical Journal in 2019